A Comprehensive (Personal And Corporate) Tax Reform Plan That’s Actually Bipartisan

When economic growth slows, it’s harder for people to find jobs, earn livable wages, save for retirement and enjoy freedoms we associate with the American dream.

Additionally, when there’s growing income inequality, any economic growth we are lucky enough to experience is enjoyed less and less by majority of Americans anyway.

Currently, our tax code is so structurally broken that it’s adding unnecessary resistance to economic growth and contributing to growing income inequality at the same time.

Addressing these problems through tax reform is the surest way we can improve people’s everyday lives. However, nothing will get fixed just by tinkering with the tax rates. Smart, effective tax reform must include structural changes to our tax code that remove this resistance to economic growth and upward mobility.

These structural changes will have systemic effects throughout the entire economy. This is where the political complexities arise.

Some smart reforms have a net-effect of raising taxes while others have a net-effect of lowering taxes. Too much of one and we aggressively raise the tax burden on our businesses and families. Too much of the other and our federal deficit balloons.

However, we can balance these reforms in a way that keeps the overall tax burden the same. This is called revenue-neutral tax reform. It encourages economic growth and is fundamentally pro-business. It also allows us to sidestep the typical “raise taxes or lower taxes debate” — which we already know gets us nowhere — while allowing us to actually fix real problems, enact meaningful solutions and finally get something productive done.

Therefore, tax reform must be looked at holistically to be maximally effective and politically feasible. And that’s where our politicians have failed in the past– by looking at either personal taxes or corporate taxes, at either raising taxes or lowering taxes. Without looking at the bigger picture, reform fails.

What follows is a bipartisan, revenue-neutral, politically feasible tax reform plan that would fix a lot of our economic problems in one fell swoop:

Summary Of Corporate Tax Reforms

- Eliminate all corporate tax exemptions and credits

- Introduce a carbon tax

- Allow dividend payments to be a tax-deductible expense just like interest payments

- Lower the corporate tax rate to 25%

- Allow 100% expensing for businesses

- Create a territorial corporate tax system

Summary Of Personal Tax Reforms

- Lower personal income tax rates to 10%, 20%, 25%

- Eliminate all credits, deductions & exemptions (ex. donations & retirement savings)

- End preferential treatment of capital gains

Restructuring The Corporate Tax Code

The US corporate tax rate is 35%, one of the highest in the industrialized world, even before state and local taxes. However, thanks to exemptions, credits and other loopholes, most companies end up paying about 25%, which is in-line with the OECD average. Large companies can usually get their rate down into the low teens.

In a perfect world, the more profit a company earns the more taxes they pay. Unfortunately with such a convoluted system, companies end up paying different tax rates completely independent from the merits of their actual business. This puts companies on an artificially uneven playing field. It also gives large companies an edge over their smaller competitors because they can afford teams of lawyers and accountants to reduce their tax burden as much as possible. This drastically increases the cost of doing business and creates a drag on economic growth.

We can fix this by restructuring our corporate tax code in the following ways:

Eliminate corporate tax exemptions and credits

Tax exemptions and credits are a result of companies lobbying Congress and are designed to affect companies and industries differently. They allow our tax code to essentially picks winners and losers based on who can lobby politicians best instead of who can provide the best value to their customers.

We can and should eliminate many, if not all corporate tax exemptions and credits. This will put all businesses and industries on a level playing field and improve the efficiencies of our economy.

Since exemptions and credits lower a company’s taxes, by removing them we’re essentially raising taxes on businesses. To make sure we don’t hurt businesses, this would need to be balanced with lowering corporate tax rates and other tax-decreasing reforms.

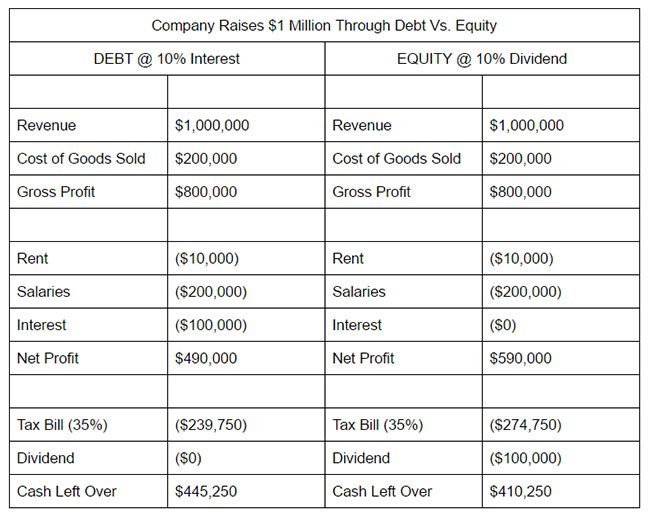

Allow for the deduction of dividend payments

Another distortion in our corporate tax code is the preferential treatment of debt over equity.

If a company needs cash, they can raise it from either debt or investors. Right now, interest paid on debt is a tax-deductible expense, which lowers the company’s tax bill. There’s no such tax benefit for paying investors a dividend — the equivalent of interest payments on debt — which encourages businesses to choose debt over equity when all else is equal.

This causes three problems: it encourages over-leveraging by favoring debt over equity; it disproportionately hurts C-Corps over S-Corps and LLCs due to double-taxation of dividends; and it discourages dividend payments to shareholders in favor of share buybacks or keeping the cash in the business. All of this could be fixed by allowing dividends to be tax-deductible.

Here’s a visual representation of how choosing debt over equity affects a business’s tax liability:

Both of these companies earned the same amount of revenue with the same amount of expenses, and the same amount of cash going in and out. But one chose to raise $1 million in debt and the other chose to raise $1 million from investors. The company that chose debt was able to keep an extra $35,000 in their business because their $100,000 interest payment reduced their taxable profit while the other company’s $100,000 dividend did not.

Companies, investors and banks are aware of the tax benefit of debt over equity. This squeezes investors while providing banks and other lenders an unfair advantage.

Most tax reform plans address this imbalance by eliminating the deductibility of interest payments — which in our example above would move the interest payment below the net profit line to where dividend payments currently are. This would fix the problem of favoring debt over equity, but it would not fix the problem of favoring certain corporate structures nor would it fix the problem of discouraging dividend payments compared to other returns for shareholders.

Fixing this imbalance by making dividends tax-deductible just like its debt counterpart can improve the efficiency of our capital markets and our overall economy.

Add A Carbon Tax

A revenue-neutral carbon tax would be pro-growth and great for business. Key word is “revenue neutral”, meaning the increase in taxes from the carbon tax must be offset by other tax-decreasing reforms so the overall net-effect on businesses is not a tax increase.

Each ton of carbon emissions cause about $20 of economic loss through higher medical costs and lost agricultural productivity. Therefore by implementing a $20 tax on each ton of carbon, we’d be helping the free market price carbon more efficiently. This would provide stronger incentives for green energy innovation than any government grant program could ever hope to achieve while also better allocating our nation’s resources for stronger economic growth.

The Tax Policy Center calculated that by implementing a $20 tax on every ton of carbon emitted and increasing that tax by 5.6% annually, we could lower the corporate tax rate by 10 percentage-points and still bring in the same amount of tax revenue. This would have the net-effect of not raising taxes on business while allowing the energy market to operate more efficiently. Like all other taxes, companies will attempt to dodge the carbon tax as well, which should be encouraged because the only side effect would be a more efficient economy and a cleaner environment.

If we want the next generation of energy technology to be developed in America so we don’t have to rely on hostile nations for our energy needs, a revenue-neutral carbon tax is the first necessary step by improving how the free market prices energy. By balancing this carbon tax with tax-reducing reforms, we’d get all the benefits without any negative side effects.

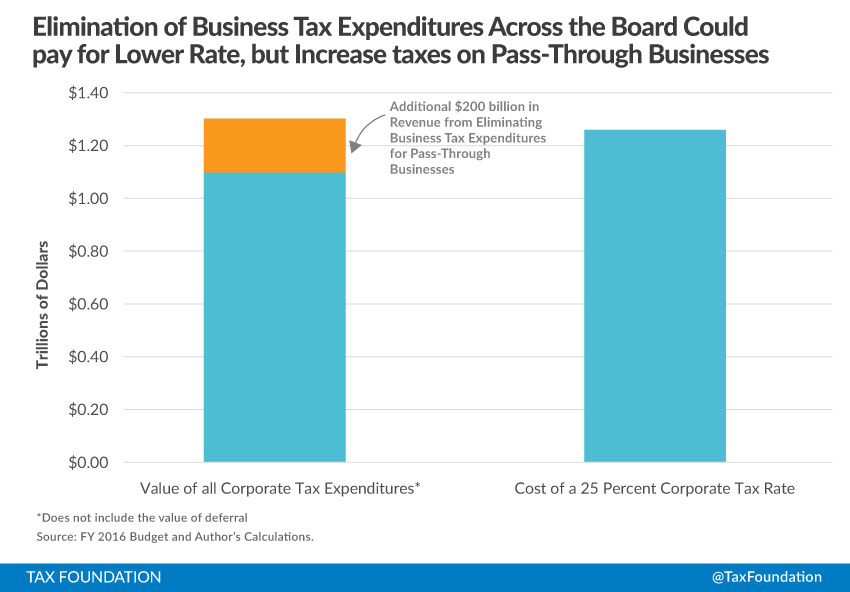

Lower The Corporate Tax Rate

Just by eliminating all exemptions and credits, studies suggest we could lower our corporate tax rate from 35% to 25% and still be revenue-neutral.

Implementing a carbon tax would allow us to lower the rate even further from 25% to 15% while remaining revenue-neutral.

Allowing dividends to be tax-deductible is a tax-break for businesses, so to balance it out the rate would have to be raised. Bringing the tax rate up from 15% to 20-25% would cover the gap, making this entire plan revenue-neutral.

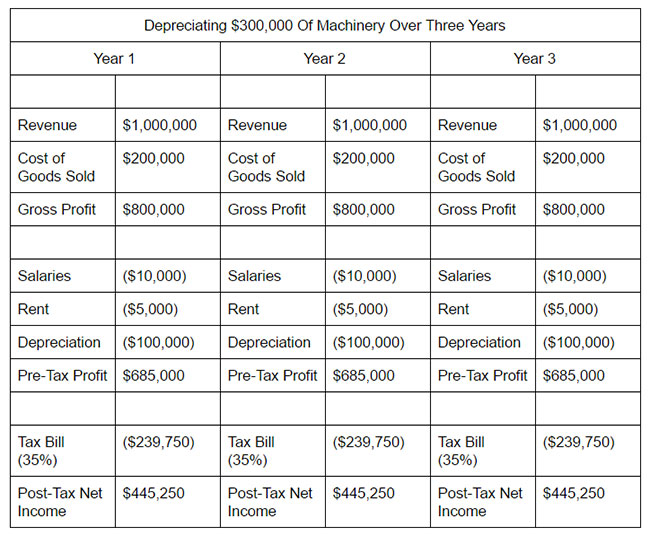

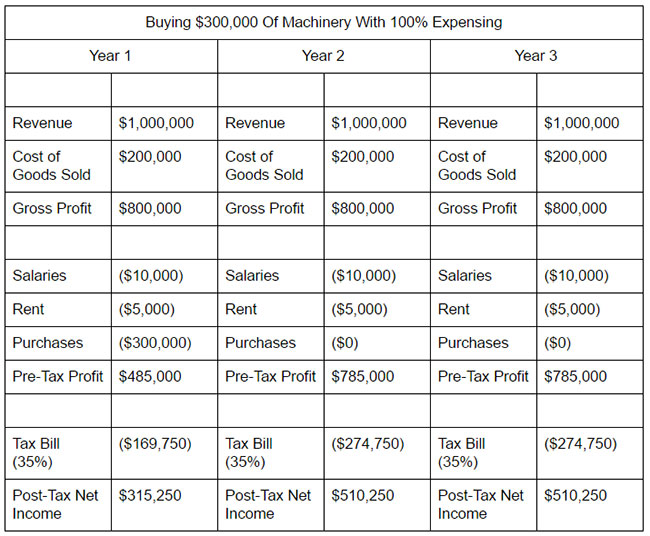

Allow 100% Expensing For Businesses

Revenues minus expenses equals the profit in which a company pays taxes on.

However, sometimes large purchases aren’t counted as expenses. The tax code typically requires spreading out the cost of purchasing large assets over multiple years.

For example, if a business purchased machinery for $300,000, instead of being a $300,000 expense in that year, the company may be forced to count it as a $100,000 expense over the next three years instead. This is called a depreciation schedule.

The IRS has complex depreciation schedules for every asset possible. This complicates bookkeeping and taxes, which adds to compliance and regulatory costs of doing business.

Here’s a visual reference–

Instead, we should allow businesses to expense their large asset purchases the same year they were purchased–

In both scenarios, the federal government still collects the same amount of tax over those three years. Therefore this may seem like a zero-sum difference, but it’s not for two main reasons.

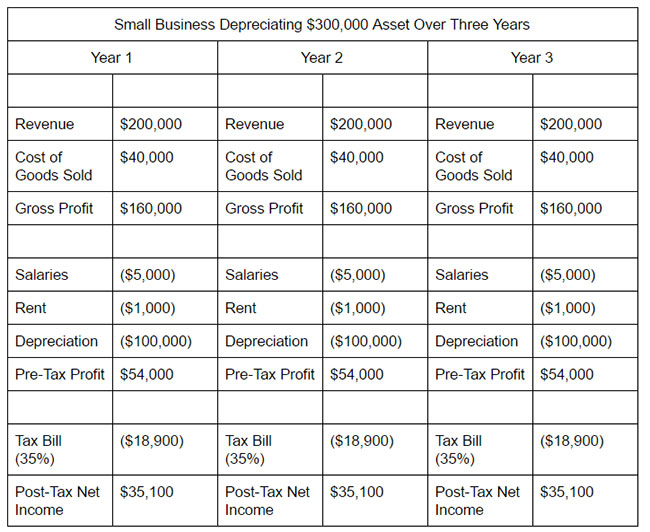

First, depreciation schedules discourage businesses from investing in themselves.

Cash flow is more representative of a company’s health than a complex tax calculation. What matters is how much cash the business has in the bank, not how much post-tax net income it has as arbitrarily defined by the IRS.

If a business purchases a large asset they feel they need, their cash flow that year will be tighter than usual. With depreciation schedules, businesses must still pay taxes like they didn’t just incur a large expense. This reduces the incentives for business to make large investments in themselves, especially small businesses, which risk running a cash-flow loss yet still having a tax bill to pay–

This small business is showing a taxable $35,100 profit in Year 1. In reality, they spent $300,000 on that asset, not $100,000. In Year 1, they actually lost $146,000 cash pre-tax, which should preclude them from paying taxes. However with depreciation schedules, they lost money and still had to pay taxes.

By allowing businesses to fully expense investments into themselves, their tax bill will be more in-line with their actual cash flow situation, which would encourage more investment.

Second, these large transactions spur economic growth. When companies buy expensive assets from other companies, those other companies end up hiring more employees and paying more in taxes. By encouraging businesses to invest in themselves and make these large transactions, we spur more economic growth.

Create A Territorial Corporate Tax System

Currently, American businesses are taxed on profits earned both within American borders as well as profits earned overseas if they bring those profits back home. To keep their tax burden low, these companies simply never bring their earnings back home and instead keep it overseas and invest it there.

If brought home, that money could pay for jobs and investment that would spur economic activity and generate even more tax revenue for the government.

Instead of taxing all income regardless of where it’s earned, moving to a territorial tax system would mean the government only taxes income earned within American borders. This is fair for businesses because they’re already taxed within the nation they earned that profit, and it’s beneficial for Americans because that money can come home and be spent on them here.

Due to these inefficiencies on how we treat international corporations, as well as our uncompetitive tax rates and overburdening tax code, many companies are inverting, or leaving America from a legal perspective in order to lower their tax burden.

One common proposal to prevent corporate inversions is to administer an exit tax on any company leaving the United States. This sounds simple, but it would actually stifle new businesses from starting in America in the first place. No international investor would willingly handcuff their cash within a country’s borders if they know they cannot easily move it if they had to.

An exit tax, or any policy to keep unwilling businesses within America, is a band-aid on a deeper wound that actually causes more harm than good.

The best way to prevent corporate inversions is to address why they are leaving in the first place– an internationally uncompetitive tax code, which puts American businesses at a competitive disadvantage to their international peers.

Reforming the whole corporate tax code would be the first part of the solution. The second would be to switch to a territorial-based system where we only tax profits earned in America and not from abroad. As the world becomes even more intertwined, it will become increasingly important how we treat international profits. A territorial-based tax system is the smart reform to address that.

Summary Of Corporate Tax Reforms

The main accomplishment of these reforms would be removing unproductive distortions that have been embedded in the tax code over time while remaining revenue-neutral if paired with the following personal tax reforms.

In doing so, a lot of the tax burden will be shifted from businesses to their shareholders, which tax experts at Harvard Business School and Oxford University both agree is a more equitable way to collect taxes for numerous reasons.

All of this combined would help spur economic activity, improve job prospects and make America much more competitive internationally.

Restructuring The Personal Income Tax Code

Majority of American businesses — especially small businesses and startups — are pass-through entities. A pass-through entity is a company that doesn’t pay corporate taxes but instead passes along the profits or losses to the owner’s personal tax returns where they are treated as any other source of personal income. Examples of pass-through entities are LLCs and S-Corps, while C-Corps are not pass through entities.

Pass-through entities account for 60% of all business income in America, employ over 50% of America’s private sector workforce and pay 37% of private sector payrolls.

Reforming only the corporate tax code would ignore over half of America’s private sector workforce who are employed by pass-through entities.

How should we reform personal income taxes to help businesses, workers and the economy? Almost exactly how President Obama’s National Commission on Fiscal Responsibility and Reform — also known as the Simpson-Bowles Plan — suggested we do.

Lower income tax rates

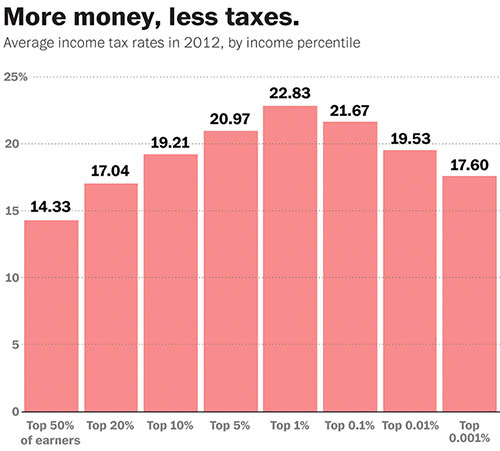

Just like corporate taxes, there is a large divergence between what the statutory and actual income tax rates are. The top income tax rate in America is 39.5%, however those earning over $62 million per year — in the top 0.001% — pay an actual tax rate of only 17.6%, which is the same actual rate as someone earning about $85,000 per year.

The benefit of having a progressive tax code — where as you earn more you pay a higher percentage of your income — is the government can afford to tax those with modest incomes less. This is incredibly beneficial for the consumer economy since more consumers would have more money to spend, which is the fundamental driver of economic growth. Give an average American $1,000 and they will spend a bit more than usual that month. Give Warren Buffett $1,000 and his spending habits would remain exactly the same.

According to the Simpson-Bowles plan, the ideal income tax brackets are 8%, 14% and 23%. With this structure, an additional benefit would be that the top income tax bracket is very close to the new proposed corporate tax rate, so there would be less distortion between pass-through entities and corporations.

Eliminate personal income tax credits, deductions and exemptions

In order to afford lower income tax rates without ballooning our federal deficit, we first need to phase out or eliminate all personal tax deductions and exemptions, with exception to charitable donations and retirement accounts. This will help low and middle class American families the most, since all deductions and exemptions are regressive, meaning they help the rich more than the poor.

Income credits are trickier since they are progressive, meaning they help lower income Americans the most. The bottom 40% of Americans actually receive money instead of paying federal income taxes, mainly due to tax credits.

Ideally, we’d eliminate all tax credits and welfare programs and implement a negative income tax in its place. This would help those in need much better than our current systems. However it’d be very difficult politically.

A more realistic option would be to eliminate all tax credits and instead provide that financial assistance outside of the tax code similar to programs like SNAP and unemployment benefits. Or we could keep some tax credits and just not lower the tax rates as much as we otherwise would be able to.

Eliminate special treatment of dividends and capital gains

The government taxes different types of personal income differently.

Salaries and wages are taxed at the normal income tax rate. Income earned through capital gains or qualified dividends are taxed at a lower preferential rate.

The prevailing argument for this special treatment is it encourages business investment, which allows for more profitable businesses that can hire more employees and pay higher wages.

While this may be true, overall it may cause more harm than good.

First, even if it does encourage business investment, it’s still essentially the government favoring one type of income over another. This creates a major loophole encouraging people to reclassify their income as capital gains in order to pay less taxes. Unfortunately this luxury is only available to business owners or people with means. These are the kinds of unintended consequences created when government provides preferential treatment of anything tax-related.

Second, if we stopped taxing capital gains and dividends at a preferential rate, we could lower income tax rates for everyone yet still bring in the same amount of tax revenue for the government. This would partially reduce the impact of eliminating the preferential treatment anyway.

With these changes, taxes for most Americans will go down, with the exception of some of the very, very wealthy. In turn, middle- and low-income Americans would keep more of their income, providing a huge boost to economic growth. Overall, this would benefit all Americans, even those at the very top that would pay a little more in taxes.

Conclusion

Historically, big technological leaps have been nearly unanimously brought to market by the private sector– computers, the internet, life-saving medicine. Developing next-generation technologies like affordable space travel, renewable energy and more life-saving healthcare will require companies to make large upfront investments and operate as efficiently as possible. By making sure our tax code is not slowing them down, we can expect America to lead with these next-generation innovations. But without corporate tax reform, that’s not so certain.

Let’s make sure the next century is as prosperous for America as the last century. We can and must reform the system so that American companies can continue to win, and that as they win, workers win and everyone wins. The future literally depends on it.